Films

The Substance (2024)

Coralie Fargeat’s latest is what happens when someone mistakes gratuitous arse shots for meaningful commentary and wraps the whole thing in the sort of pseudo-intellectual packaging you’d find on overpriced skincare products.

Published

4 months agoon

By

ScreenDim

Right, let’s talk about “The Substance,” a film that promises to explore the horrors of ageing, vanity, and self-destruction but instead delivers two hours of what can only be described as a perfume advertisement that’s been fed a steady diet of film theory essays and developed delusions of grandeur. It’s body horror for people who think body horror should come with subtitles explaining why it’s important.

Someone at Working Title looked at the concept of a woman literally splitting herself in two to recapture youth and thought: “You know what this needs? More confusion about basic narrative logic and approximately seventy-three lingering shots of buttocks.” The result is a film that functions like a philosophy seminar conducted by someone who’s never actually read any philosophy but has seen a lot of very artistic nude photography.

The premise is genuinely intriguing: Elisabeth, a woman confronting the twilight of her career and youth, discovers a mysterious substance that allows her to create a younger, more beautiful version of herself called Sue. It’s a concept ripe for exploration of identity, the male gaze, society’s obsession with youth – all the meaty psychological horror you could want. Instead, we get a film that seems more interested in photographing the results of good genetics than actually examining what any of this means.

The fundamental problem is that “The Substance” can’t decide what it wants to be. Is it a psychological thriller? Body horror? An art installation that’s somehow wandered into a cinema? The film approaches these questions like a particularly confused chatbot that’s been trained on equal parts David Cronenberg and Victoria’s Secret catalogues, resulting in something that feels like it was assembled by an algorithm designed to win film festival awards whilst simultaneously selling anti-ageing cream.

Let’s address the elephant in the room: the relationship between Elisabeth and Sue makes about as much sense as trying to explain quantum physics using only emoji. Sometimes they share memories, thoughts, and experiences like they’re the same person experiencing a very expensive dissociative episode. Other times they behave like completely separate individuals who just happen to be sharing real estate in the same supernatural rental agreement. The film never commits to an explanation, and not in a clever, thought-provoking way, but in a “we didn’t bother working this out during the writing process” way.

This isn’t ambiguity; it’s narrative negligence dressed up as artistic choice. By the fourth or fifth “wait, are they the same person or not?” moment, you begin to suspect that even the characters themselves have given up trying to understand the rules of their own existence. It’s like watching someone play a video game where the controls keep changing but nobody’s bothered to update the instruction manual.

The performances are perfectly adequate, which is rather like saying a house fire is perfectly warm. Elisabeth’s portrayal of a woman grappling with obsolescence is competent enough, whilst Sue spends most of her screen time looking like she’s posing for the sort of high-end magazine shoot that makes you question your life choices. But no amount of committed acting can save a script that’s more interested in appearing profound than actually being coherent.

And Christ, let’s talk about the male gaze situation, because “The Substance” is so drenched in it you could wring it out and water a small garden. The sheer volume of lingering shots of Sue’s body reaches levels that would make a teenage boy’s browser history look restrained. The film claims to be making a statement about objectification whilst simultaneously objectifying its own characters with the enthusiasm of someone who’s just discovered slow-motion photography and lost all sense of proportion.

Every frame seems designed to showcase Sue’s physique in ways that would make a perfume commercial director blush. It’s the cinematic equivalent of someone explaining feminism whilst staring directly at your chest – technically hitting the right talking points but missing the fundamental concept so completely that you wonder if they’re taking the piss.

The film pretends this hypersexualisation serves some greater artistic purpose, but mostly it feels like directorial self-indulgence masquerading as social commentary. You could remove half these shots and not only lose nothing of narrative value, you’d probably improve the film by eliminating the constant distraction of wondering whether you’ve accidentally stumbled into someone’s very expensive masturbatory fantasy.

For a film that bills itself as psychological body horror, “The Substance” delivers about as much genuine horror as a yoga class conducted by someone who’s read too many wellness blogs. There are moments of unease scattered throughout like raisins in a particularly disappointing bread, but they’re overwhelmed by the film’s relentless need to admire its own supposed cleverness.

The actual horror elements feel perfunctory, as if someone realised halfway through production that they were supposed to be making a scary film and hastily inserted a few “disturbing” moments between the artistic nudity and philosophical posturing. When the body horror finally arrives, it’s competently executed but lacks the visceral impact that comes from proper setup and character investment.

The film’s obsession with its own aesthetic prevents it from committing to any particular genre or tone. It wants to be “The Fly” meets “Black Swan” but ends up more like “Showgirls” meets a particularly pretentious TED talk about the patriarchy. Every potentially effective horror moment is immediately undercut by the film’s desperate need to remind you that this is Art with a capital A and possibly a small sculpture next to it.

The visual design is undeniably striking – all sleek surfaces and unsettling clinical environments that look like the sort of spa where you’d go to have your soul professionally exfoliated. But visual sophistication without narrative coherence is just expensive wallpaper, and “The Substance” is essentially a very pretty film about absolutely nothing happening very slowly in beautiful lighting.

The climax, when it finally arrives after what feels like seventeen hours of watching people look meaningfully at mirrors, resolves precisely nothing. Characters make choices that seem motivated more by the need to create visually interesting set pieces than by any logical progression of their established personalities or desires. It’s like watching someone solve a jigsaw puzzle by eating half the pieces and declaring the remaining chaos a statement about modern society.

“The Substance” represents everything wrong with contemporary “elevated” horror – films so convinced of their own importance that they forget to actually function as entertainment. It’s what happens when you take a genuinely interesting premise and run it through a focus group consisting entirely of people who buy £400 face cream and consider it a personality trait.

The film mistakes confusion for complexity, repetition for emphasis, and nudity for profundity. It’s a movie that desperately wants to say something meaningful about ageing, beauty standards, and female identity but gets so distracted by its own reflection that it forgets to actually say anything at all.

By the time the credits roll, you’re left with the distinct impression that you’ve just watched someone spend two hours explaining a joke that wasn’t funny to begin with, using PowerPoint slides featuring artistic shots of human anatomy. It’s the cinematic equivalent of paying premium prices for a philosophy course taught by someone who’s confused Instagram captions with actual insight.

“The Substance” is proof that having something to say and actually saying it are two entirely different things. It’s a film that confuses style with substance – which, given the title, represents either profound irony or complete lack of self-awareness.

You may like

Films

Until Dawn (2025)

David F. Sandberg’s time-loop horror clusterfuck is like watching someone play Russian Roulette with a Rubik’s Cube whilst being chased by a photocopier that’s achieved sentience and developed a taste for human flesh

Published

1 month agoon

May 29, 2025By

ScreenDim

Right, let me get this straight. Someone at Sony Pictures looked at a video game about teenagers being systematically murdered by supernatural bastards on a snowy mountain and thought: “You know what this needs? More death. Specifically, the same death. Over and over again. Like a horrific breakfast cereal commercial directed by the Marquis de Sade.”

And somehow, against all cosmic logic and basic narrative physics, they’ve gone and made it work.

“Until Dawn” – the film, not the game that spawned it like some digital parasitic twin – is what happens when you cross “Groundhog Day” with “The Descent” and then feed the resulting abomination a steady diet of energy drinks and expired painkillers. It’s a time-loop horror film that functions like a demented slot machine: pull the lever, watch beautiful people die horribly, rinse, repeat, occasionally win a stuffed wendigo.

I will say, right off the bat, I went into it expecting it to be an adaptation of the game, which threw me off at first. But the more I thought about it, the more the film grew on me.

The premise is beautifully, almost pornographically simple. A group of attractive young people – because ugly people apparently don’t get trapped in supernatural time loops, which seems discriminatory but there we are – venture into a remote valley searching for a missing sister. They find themselves in what appears to be a visitor centre designed by someone who clearly studied architecture at the University of Obviously This Is A Trap. Come nightfall, they’re systematically butchered by various threats that change with each reset like a Netflix algorithm that’s developed homicidal tendencies.

One night it’s a masked slasher straight out of central casting’s “Generic Killer” department. The next, it’s wendigos that look like someone fed a deer through a paper shredder and then reassembled it using only spite and terrible life choices. Then there are creatures that emerge from the ground like the world’s worst surprise party, and at one point – and this is genuinely inspired lunacy – the water itself becomes weaponised, turning people into human fireworks displays that would make “Scanners” weep tears of jealous admiration.

Director David F. Sandberg, previously responsible for making us all afraid of light switches in “Lights Out,” has essentially created a horror film that functions like a particularly sadistic choose-your-own-adventure book, except the reader is unconscious and the choices are being made by a committee of psychopaths with a fetish for dramatic irony.

The genius of it – and yes, I’m using the word “genius” about a film where people repeatedly die because they make the sort of decisions that would embarrass a concussed lemming – is that it shouldn’t work. Time-loop films are notoriously difficult to pull off without becoming either insufferably repetitive or so convoluted they require a PhD in theoretical physics to follow. “Until Dawn” sidesteps this by embracing the repetition and making it the point. Each reset isn’t just a do-over; it’s a completely different flavour of nightmare, like a box of chocolates curated by H.P. Lovecraft.

The film gleefully acknowledges its own absurdity. When your protagonists realise they’re trapped in what amounts to a supernatural game of musical chairs where the music is screaming and the chairs are made of teeth, the only sensible response is to lean into the madness. Ella Rubin’s Clover navigates this recursive hellscape with the sort of determined practicality you’d normally associate with someone trying to assemble IKEA furniture whilst being periodically attacked by bears.

The supporting cast – Michael Cimino, Odessa A’zion, Ji-young Yoo, and Belmont Cameli – manage to avoid the typical trap of horror protagonists, namely being so insufferably stupid that you find yourself rooting for the monsters. These characters actually learn from their mistakes, which in a time-loop scenario is like watching evolution in fast-forward, except with more dismemberment.

Peter Stormare returns from the original game, presumably because someone at Sony realised that if you’re going to make a film this aggressively bonkers, you need at least one actor who can deliver exposition about supernatural curses whilst maintaining the sort of gravitas normally reserved for Shakespearean soliloquies about the nature of existence.

The film’s greatest achievement is its gleeful embrace of B-movie sensibilities whilst maintaining enough technical sophistication to prevent it from descending into pure camp. It’s horror comfort food – familiar enough to be satisfying, strange enough to keep you engaged, and just bloody enough to remind you that yes, people are definitely dying here, even if they’ll be back in twenty minutes looking confused and slightly dishevelled.

Critics have complained about the repetitive nature, which is rather like criticising a washing machine for being circular. The repetition IS the point. Each loop reveals new layers of the mythology, new aspects of the threat, new ways for attractive people to meet spectacularly unpleasant ends. It’s like watching someone slowly peel back the layers of an onion, except the onion is made of nightmares and occasionally explodes.

The film’s relationship with its source material is refreshingly pragmatic. Rather than attempting a slavish adaptation that would essentially be a ten-hour game compressed into ninety minutes of confusion, Sandberg and writers Gary Dauberman and Blair Butler have created something that exists in the same universe whilst telling its own story. It’s the difference between a cover version and a remix – technically related, but serving different purposes.

Where the game relied on player choice to drive narrative tension, the film substitutes the random brutality of fate. You can’t save these characters through careful decision-making; you can only watch them adapt, learn, and slowly piece together the rules of their particular corner of hell. It’s oddly liberating, like watching someone else navigate a particularly vindictive video game whilst you eat crisps and shout unhelpful advice.

The wendigos deserve special mention as perhaps the most effectively realised movie monsters in recent memory. They move with the sort of predatory grace that suggests they’ve studied ballet but only the parts involving sudden, violent movement. When they emerge from the shadows – and they do emerge, frequently and enthusiastically – they bring with them a sense of ancient hunger that makes even the jump scares feel earned rather than cheap.

The film’s structure allows for a surprising amount of world-building without resorting to tedious exposition dumps. Each reset reveals new details about the valley’s history, the nature of the curse, and the various supernatural entities that call this place home. It’s environmental storytelling at its most effective – you learn about this world by watching people die in it repeatedly, which is both darkly comic and oddly efficient.

The special effects work is impressively practical, with CGI used to enhance rather than replace physical effects. When people explode – and they do explode, magnificently – it feels appropriately messy and consequential. The various monsters are tactile, weighty things that occupy space convincingly rather than looking like expensive screensavers.

What elevates “Until Dawn” above its B-movie origins is its understanding that repetition, rather than being narrative death, can be narrative rebirth. Each loop functions as both climax and setup, ending and beginning. It’s a film that eats its own tail and somehow manages to grow stronger in the process.

The climax, when it finally arrives, feels genuinely earned rather than arbitrary. The characters have learned enough about their situation to make informed choices, and the audience has seen enough variations to appreciate the significance of their final gambit. It’s like watching someone finally solve a Rubik’s Cube after you’ve seen them fumble with it for ninety minutes, except the cube is cursed and solving it incorrectly results in death by supernatural entities.

“Until Dawn” succeeds by being precisely as complicated as it needs to be and no more. It’s a film that knows exactly what it is – a gleefully violent playground for exploring variations on familiar themes – and executes that vision with the sort of confident craftsmanship that makes even the most ridiculous moments feel oddly plausible.

The film’s greatest magic trick is making you forget you’re watching the same basic scenario repeated with variations. By the third or fourth loop, you’re not thinking about repetition; you’re thinking about possibility. What new horror will tonight bring? How will the characters adapt? Which familiar face will die in an entirely new and creative way?

“Until Dawn” is a film that shouldn’t work, made by people who clearly understand exactly why it shouldn’t work, who then proceed to make it work anyway through sheer bloody-minded commitment to their own demented vision. It’s like watching someone successfully perform surgery with a spoon – technically inadvisable, practically impossible, but undeniably impressive when pulled off with sufficient skill and audacity.

In a landscape of horror films that often prioritise innovation over execution, “Until Dawn” succeeds by taking familiar elements and arranging them in combinations that feel both nostalgic and fresh. It’s a film that respects its audience’s intelligence whilst never forgetting that sometimes the best horror comes from the simplest premise executed with maximum conviction.

The result is a film that works precisely because it embraces its own absurdity without ever winking at the audience. It’s sincere about its own ridiculousness, committed to its own chaos, and confident enough in its own premise to trust that audiences will follow it down whatever rabbit holes it chooses to explore.

“Until Dawn” is proof that sometimes the best way to avoid repeating past mistakes is to repeat them intentionally, with style, until they become something entirely new. It’s a film that transforms repetition from weakness into strength, familiarity into freshness, and death into the beginning of possibility.

In short, it’s bloody brilliant.

Films

Lilo & Stitch (2025)

Yes, the lead actress is good. Yes, kids might enjoy it. Yes, someone on the production team probably had the best of intentions. But intent doesn’t make a movie good. And this movie? Is. Not. Good.

Published

1 month agoon

May 22, 2025By

ScreenDim

I am not happy.

Lilo & Stitch (2025) is the latest victim in Disney’s increasingly joyless remake assembly line, and it’s safe to say: Elvis isn’t the only one rolling in his grave.

This remake isn’t just disappointing—it’s borderline offensive in how it mishandles the original’s emotional core. The 2002 Lilo & Stitch was vibrant, offbeat, tender, and unlike anything else Disney had done at the time. It blended themes of loss, found family, and alien chaos with humour, cultural specificity, and actual personality. The 2025 version, by contrast, feels like it was assembled by a neural network trained exclusively on Disney+ thumbnails.

Let’s start with the changes. You know how the original had a quirky, grounded warmth—characters who felt like real people, despite the extraterrestrials? That’s gone. Now we have a smoothed-over, overly lit, airbrushed version of Hawaii that looks more like a sanitized tourist brochure than a lived-in home. The rough edges that gave the original heart have been sanded down and focus-tested into oblivion.

Lilo no longer rants about how not giving Pudge the fish his weekly peanut butter sandwich will make her an abomination.

Lilo no longer beats the crap out of Myrtle—now she just pushes her off stage.

I have a whole list of these but I’d be sat here for hours typing them out.

Stitch, meanwhile, looks like he escaped from a low-budget Sonic the Hedgehog fan film in 2014 and wandered onto the wrong soundstage.

The physical comedy doesn’t work because Stitch doesn’t have weight. He’s a floating CGI asset dropped into scenes like an afterthought. He might as well have “property of Disney+” watermarked on his forehead.

The film clocks in at around 100 minutes, but somehow still feels longer. And yet, some scenes feel rushed, like the filmmakers were just ticking boxes. It’s like watching an abridged version of a movie you actually liked, directed by someone who skimmed the Wikipedia plot summary the night before shooting.

Let’s pause to remember what made the original Lilo & Stitch special: it was weird. It was messy. It was emotionally honest in ways Disney usually avoids. It had Elvis on the soundtrack, and actual stakes in the relationships.

This version? It’s afraid of weird. It’s terrified of emotional honesty. Everything’s been rounded off, polished up, and stripped of any quirk that might alienate a potential viewer in the Midwest. Even Nani feels reduced—her complex role as a struggling guardian-sister rewritten into Generic Young Woman Who Tries Hard. There’s no edge. No bite. No soul.

Worse, this film treats the original audience like we don’t matter. It gestures toward nostalgia with a few half-hearted references, but mostly screams: “This one’s for the new kids!” But here’s the thing—kids deserve better than this. Kids are smart. Kids loved the original Lilo & Stitch because it was different.

This isn’t different. This is safe, stale, and sanitized.

Now, about the voices.

Let’s start with Jumba. In the original, he was a gloriously bizarre mad scientist with a vaguely Eastern European accent and gleeful menace. In this version, he has—drumroll—an American accent. It’s jarring and takes you right out of the movie. Why American? Who knows. Maybe the studio thought kids couldn’t handle anything foreign-sounding. But it completely flattens the character. He’s no longer chaotic brilliance—he’s just a weird uncle who works in IT and recently discovered protein powder.

And it’s just Zach Galifianakis. Not putting on a voice. Not even attempting an accent. Just… Zach.

Then there’s Pleakley.

They’ve dumbed him down—way down. In the original, he was campy, neurotic, and weirdly endearing. Now? He’s just dumb. Like TikTok-filter dumb. Like “he wears a cowboy hat because he misunderstood the word ‘cowboy’” dumb. (Yes, that’s a real joke in the movie.)

This might have worked as a 15-second YouTube short back in 2010. Here, it’s just another brick in the wall of tonal flatness.

So what are we left with?

A visually flat, emotionally shallow, hyper-sanitized remake that mistakes content for connection. A film that rips out the heart of a classic and replaces it with a plastic replica—perfectly shaped, but utterly lifeless.

Yes, the lead actress is good.

Yes, kids might enjoy it.

Yes, someone on the production team probably had the best of intentions.

But intent doesn’t make a movie good. And this movie?

Is. Not. Good.

Films

Final Destination: Bloodlines (2025)

Final Destination: Bloodlines isn’t bad. It’s just missing the atmosphere—the creeping, skin-prickling feeling that you’re being watched by something inescapeable.

Published

1 month agoon

May 22, 2025By

ScreenDim

After a twelve-year hiatus and a seemingly endless chain of false restarts, Final Destination has clawed its way out of the cinematic grave for another dance with the Reaper in Final Destination: Bloodlines. Directed by Adam B. Stein and Zach Lipovsky, Bloodlines is exactly what you’d expect from the sixth installment of a franchise that peaked with a guy being liquefied by a pool drain: bloody, occasionally clever, mostly ridiculous, and… fine. Just fine.

Not great. Not awful. Fine.

The film centers on Stefanie (played with respectable mid-level scream queen energy by Brec Bassinger), a college student plagued by violent nightmares. These visions, as is tradition in Final Destination lore, turn out to be harbingers of doom. Stefanie, sensing her family might be next in Death’s never-ending group project, heads home in a frantic bid to save them. What follows is a familiarly structured series of panic attacks, suspiciously timed gusts of wind, household items conspiring to kill people, and a vaguely metaphysical game of “hot potato” with the concept of fate.

Let’s start by giving Bloodlines its flowers, because while it’s not reinventing the wheel, it’s at least keeping it spinning.

One thing this film does well—surprisingly well, actually—is its gore. The kills are gnarly, as they should be. In Final Destination fashion, they remain Rube Goldberg nightmares soaked in tension, where every creaky step, loose screw, or casually misplaced fork could mean sudden and excruciating death.

There are also some genuine surprises sprinkled in. The film plays a little fast and loose with the death order, and a few kills subvert expectations just enough to earn a slow clap.

And then there’s Tony Todd. The man, the myth, the mortician. Returning once again as the ominous voice of Death (or at least its HR representative), Todd brings his usual silky-voiced gravitas. His appearance here is brief but memorable, and without getting too spoilery: it’s a graceful, oddly sweet exit. It’s clear the filmmakers wanted to honor his contributions, and they succeeded. He’s the soul of this franchise, and Bloodlines knows it.

Unfortunately, once you get past the splatter and the sentiment, Bloodlines starts to fall apart under closer scrutiny. The main issue? It just doesn’t feel… spooky.

Earlier entries in the Final Destination series succeeded because Death felt like a character—unseen, omnipresent, angry. There was a dread that lingered after the jump scares. A fan would turn on by itself and you’d flinch. A nail sticking out of a board would have you clenching. The world became dangerous. Everything was a trap.

But in Bloodlines, Death doesn’t really feel like it’s hunting anyone. It’s more like it set some booby traps and then went out for a smoke break. The dread is missing. Instead of that creeping inevitability, you just kind of wait around for the next blood geyser. It’s not ineffective, but it lacks that eerie atmosphere that made the original films so memorable.

Even the signature premonition sequence—the grand disaster that kicks off each film—is a bit underwhelming. In a franchise that gave us collapsing rollercoasters and racetrack carnage, this one feels a bit… budget.

It wouldn’t be a Final Destination movie without a cast of doomed young people whose names you forget five minutes after they die. And Bloodlines continues that proud tradition with a roster of characters that are, at best, functional.

Stefanie is a solid protagonist—smart enough to figure out the pattern, vulnerable enough to still make questionable decisions, and just engaging enough to keep us watching. But everyone else? Walking meat puppets. There’s the sarcastic best friend, the sweet-but-doomed younger sibling, the skeptical uncle who definitely wasn’t going to make it past Act Two. You know the drill. They’re not bad, but they’re barely there.

Worse, the dialogue often sounds like it was ripped straight from a horror writing workshop in 2011. There’s a lot of “You don’t understand!” and “It’s happening again!” and at least one person yells “It’s not real!” moments before… y’know…

Bloodlines attempts to add some lore to the franchise, which is usually a red flag—and, surprise, it mostly is. The premise suggests that Stefanie’s family is cursed, and that Death’s design has somehow taken root in her bloodline. Cue vague metaphysical references and cryptic dreams about clocks and blood and, of course, Tony Todd standing in a doorway looking disappointed.

This new mythology is meant to expand the world, but it mostly just muddies it. What made the original formula work was its brutal simplicity: someone cheats death, death gets petty and takes them out one by one. Done. This new “family curse” angle tries to deepen the lore but ends up raising more questions than it answers. Why this family? Why now? How does the substance of the dreams tie into the mechanics of Death’s design? The movie gestures toward answers but never really delivers.

And again, let’s circle back to that lack of spooky tension. Even if the new lore worked, the absence of Death as a truly menacing force undermines the whole thing. Without that looming, invisible threat, Final Destination becomes just a snuff film with better lighting. Think “Saw” if Jigsaw just set up devious Rube Goldberg machines instead of his usual games.

This deserves repeating: the send-off for Tony Todd is genuinely lovely. In a franchise not exactly known for its emotional nuance, it’s surprising how well this moment lands. It’s quiet, respectful, and weirdly touching.

It also unintentionally underscores how much the franchise has relied on him to give it weight. Without Todd’s booming voice and cryptic warnings, Bloodlines feels a little hollow. Like Death itself called in sick and left some interns running the shop.

Final Destination: Bloodlines isn’t bad. It’s a serviceable entry in a franchise that’s always been a bit hit-and-miss. It has the kills. It has the chaos. It even has a few surprises. But what it doesn’t have is the atmosphere—the creeping, skin-prickling feeling that you’re being watched by something you can’t escape.

Instead, it plays like a checklist:

✔ Dramatic premonition

✔ One character who becomes obsessed with figuring out the pattern

✔ Final girl running around with conspiracy walls

✔ Surprise kill after a fakeout

✔ One or two deaths so ridiculous they almost feel like satire

It’s fine. And maybe, after so many years, “fine” is good enough. But for fans who’ve been waiting over a decade for Death to reclaim its throne, Bloodlines feels like more of a warm-up than a comeback.

Trending

-

Films1 year ago

Films1 year agoMadame Web (2024)

-

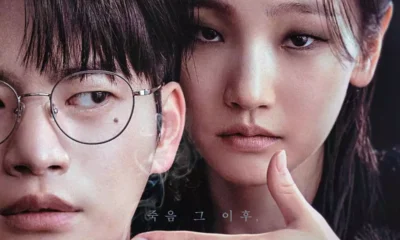

TV Shows1 year ago

TV Shows1 year agoDeath’s Game (2023)

-

TV Shows1 year ago

TV Shows1 year agoScraping the Barrel

-

Films2 years ago

Films2 years agoThe Little Mermaid (2023)

-

Video Games1 year ago

Video Games1 year agoThe Last of Us (2013 PS3)

-

Films8 months ago

Films8 months agoSalem’s Lot (2024)

-

Films1 year ago

Films1 year agoImaginary (2024)

-

Films1 year ago

Films1 year agoNight Swim (2024)